ARM Assembly - Zero to Hero in 22 Days

December 27, 2022Introduction

Who Am I? - Akram Ansari (https://mdakram.com/)

I have been teaching ARM assembly to university students. This article is adapted from the tutorial material for a Computer Science Course - CPSC355 that I taught in 2022 and is meant to teach the basics of assembly, c and the inner working of a computer application. The article will focus on understanding how a computer program is written and how that program is understood and executed by the processor. We will write assemble for the 64-bit ARMv8 architecture CPU. We will also understand what the binary code of a program written in C looks like. We will run the program in a Linux OS.

The source code for the examples and exercise solutions can be found in the repo : https://github.com/mdakram28/cpsc355.

How to follow?

Try to run the code given as examples and also attempt to solve the exercises. The sessions are meant to be covered in 1 day each and would take a maximum of 30 minutes per session. It also has 6 break days included. Cover the material at the suggested pace to get maximum retention of the concepts.

Session 01: Setup

01.1. Setting up your workspace

- You need to have a computer running any flavour of linux runnning.

- Install necessary dependencies to run arm binaries on an x86 system. https://azeria-labs.com/arm-on-x86-qemu-user/

01.2. Intro to the linux shell and VIM

Basic Shell Commands

# This is a comment # 1. Print Directory Content ls # 2. Enter a Directory cd <Directory> # 3. Exit The current directory cd .. # 4. Crate a file touch <filename> # 5. Edit or create a file using vim vim <filename> # Clear the screen clear # Make a new directory mkdir <directory> # Delete a file rm <filename> # Delete a directory rm -r <directory>VIM

Operating modes in vim editor:

- Command Mode: By default, command mode is on as soon as the vim editor is started. This command mode helps users to copy, paste, delete, or move text. We should be pressing [Esc] key to go to command mode when we are in other modes.

- Insert mode: Whenever we try to open vim editor, it will go to command mode by default. To write the contents in the file, we must go to insert mode. Press ‘I’ to go to insert mode. If we want to go back to command mode, press the [Esc] key.

01.3. Compiling Your first C program

- Compiling a C program

- Write your C program in a file with the extention

.c(Not a requirement). - Enter the command to compile your C program into an

executable binarygcc codefile.c -o outfile.out - Run the compiled binary.

./outfile.out

- Write your C program in a file with the extention

01.4. Hello World in C

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

printf("Hello World\n");

return 0;

}

01.6. Exercise

Write a C program to convert celcius to fahrenheit

- Get the current temperature in fahrenheit from the user

- Convert it to celsius

- Print the converted temperature

$$ C = \frac{(F - 32) * 5}{9} $$

Solution

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

float temp_f, temp_c;

printf("Enter temperature in fahrenheit: ");

scanf("%f", &temp_f);

temp_c = ((temp_f - 32) * 5) / 9;

printf("Temperature in Celsius: %f\n", temp_c);

return 0;

}

Session 02: C for Java Developers

02.1. What's the same? What's different?

- What's the same?

- Values, Types (more or less), literals, expressions

- Variables (more or less)

- Conditionals:

if,switch - Iteration: while, for, do-while, but not for-in-collection (“colon” syntax)

- Call-return (methods in Java, functions in C): parameters/arguments return values

- Arrays (with one big difference)

- Primitive and reference types

- Typecasts

- Libraries that extend the core language (although the mechanisms differ somewhat)

- Whats Different

- No classes or objects

- Arrays are simpler

- C-Strings are much more limited

- No Collections

- No garbage collection

- Pointers !! (Memory addresses)

02.2. Data Types

Primitive Types

java C int int short short long long float float double double char char byte N/A boolean N/A Strings In C, strings are simply arrays of chars. That’s it. The following allocates a string that can hold 32 characters:

char name[32];You can use the string literal syntax to initialize a character array, and if you do, the C compiler is smart enough to figure out the length for itself

char name[] = "George";C-strings are null terminated

02.3. Input and Output

printf - https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man3/printf.3.html

Syntax: printf(char * format, ...variable_list)

format: A character string composed of zero or more ordinary chracters (not %) and format specifiers (starting with %).

variable_list: A list of values to replace in place of format specifiers according to the given format

Example:

int num = 2; printf("%d", num); float num2 = 3.1415926; printf("PI = %f", num2); // PI = 3.1415926 printf("PI (2 decimal places) = %.2f", num2); // PI (2 decimal places) = 3.14 char str[] = "Sheldon Cooper"; printf("Name :: %s", str); // Name :: Sheldon Cooper

scanf - https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man3/scanf.3.html

Syntax: scanf(char *format, ...variable_pointers)

format: A character string composed of zero or more ordinary chracters (not %) and format specifiers (starting with %).

variable_pointers: Memory addresses of variables to store the input

Example:

int num; print("Enter a number : "); scanf("%d", &num); char str[10]; scanf("%9s", str); printf("Entered string : %s", str);

getchar - https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man3/getchar.3p.html

get a byte from standard input stream

Example:

#include <stdio.h> int main () { char c; printf("Enter character: "); c = getchar(); printf("Character entered: "); putchar(c); return(0); }

putchar - https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man3/putchar.3p.html

put a byte on the standard output stream

Example:

#include <stdio.h> int main () { char ch; for(ch = 'A' ; ch <= 'Z' ; ch++) { putchar(ch); } return(0); }02.4. String utilities

strlen - https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man3/strlen.3.html

- calculate the length of a string

strcpy - https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man3/strncpy.3.html

- copy a string

Example:

char str[] = "Hello World"; char str2[32]; printf("String length = %d", strlen(str)); strcpy(str2, str); printf("Copied string : %s", str2);

References

- C for Java Programmers (George Ferguson) - https://www.cs.rochester.edu/u/ferguson/csc/c/c-for-java-programmers.pdf

Session 03: Intro to Assembly & GDB

03.1. Writing and compiling an assembly program

Save your assembly code with the file extension

.sCompile the

.sassembly code file to.oexecutable binary file.gcc code_file.s -o code_file.o -g- The

-gflag tells gcc to add debug information to the binary executable. Use it when you plan to debug the created binary using gdb.

- The

03.2. ARM Assembly Example

Proram to print hello world 10 times.

# AARCH64 assembly tutorial example 01

// Tell GCC to use printf function from outside this code

.extern printf

fmt:

.string "x19 = %d Hello World!\n" // String to send to printf

// Main function

.balign 4 // Align instructions to word

.global main // Make main function visible to outside this code

main:

stp x29, x30, [sp, -16]! // Save FP and LR to stack

mov x29, sp // Update FP to current SP

// Initialize loop counter

mov x19, #1; // x19 starts from 1

loop_top: // Loop starts here

cmp x19, #10 // Compare x19 to 10

b.gt loop_end // If x19 > 10 then goto loop_end

// Call printf external function

ldr x0, =fmt // First argument is the pointer to format string

mov x1, x19 // Second argument is the integer to replace "%d"

bl printf // Call printf

add x19, x19, #1 // Increment loop counter

b loop_top // Repeat loop

loop_end:

b exit // Goto Exit (Not needed here)

exit:

// return 0

mov x0, 0 // Return value 0 is stored in x0

ldp x29, x30, [sp], 16 // Restore FP and LR from stack pointer

ret // Go back to the callee

03.3. Debugging using gdb

To open the program in gdb:

gdb my_asm.o

03.4. Useful gdb commands

| Full command | Abbreviation | Description |

|---|---|---|

break temp.c:28 |

b temp.c:28 |

Set a breakpoint in the file temp.c at line 28 |

break flabel_name |

b label_name |

Set a breakpoint at the start of the label_name label. |

run |

r |

Start the program and run until the end of the program/the program crashes/the next breakpoint/the next watchpoint (if the program is already running, this command will tell the program to start from the beginning) |

continue |

c |

Continue running until the end of the program/the program crashes/the next breakpoint/the next watchpoint |

next/nexti |

n/ni |

Execute the current command, and move to the next command in the program. The i variant will execute a single instruction instead of a line. |

step/stepi |

s/si |

Step through the current command, but if this command is a function call, then go to the first line of that function. The i variant will execute a single instruction instead of a line. |

print x |

p x |

Print the value of the register x. |

print/x x |

p/x x |

Print the value of the register x in hexadecimal |

x addr |

Inspect memory at address (Prints 32 bytes hex value by default) | |

x/s addr |

Print the string starting at addr and ending with a \0 |

|

info breakpoints |

i b |

Display information about all declared breakpoints |

info registers |

i r |

List all registers and their values. |

| info registers x19 | i r x19 | Print the value of regsiter x19 |

delete breakpoints |

delete |

Delete all breakpoints that have been set |

clear label_name |

Deletes the breakpoint set on label_name |

|

quit |

q |

Exit gdb |

Session 04: Control Flow in Assembly

04.1. Define and Macros

- The define statement can create alternate name for registers.

// This will tell the assembler to replace all x_r to x19 define(x_r, x19) - The commands

.macroand.endmallow you to define macros that generate assembly output. For example, this definition specifies a macro sum that puts a sequence of numbers into memory:.macro increment reg add \reg, \reg, 1 .endm

04.2. Branch Instruction and Condition Codes

- Conditional branch statements use the condition falgs to make a decision.

- These condition flags are set or unset depending on the result of a compare instruction. i.e.

cmp

Example:

cmp x19, x20

b.eq some_label

The cmp instruction compares the values of two registers or a register and a value and the b.eq instruction jumps to some_label if the compared values were equal.

Other branching instructions:

- b.eq (==)

- b.ne (!=)

- b.gt (>)

- b.lt (<)

- b.ge (>=)

- b.le (<=)

04.3. Loops

do-while loop (post-test loop)

Example: C Code:

long int x; x = 1; do { // Loop body x++; } while(x <= 10);Equivalent Assembly Code:

mov x19, 1 top: // Loop Body // ... add x19, x19, 1 cmp x19, 10 b.le top

while loop (pre-test loop)

- Example

C Code:

Equivalent Assembly Codelong int x; x = 0; while (x<10) { // Loop body x++; }define(x_r, x19) mov x_r, 0 b test top: // Loop Body // ... add x_r, x_r, 1 test: cmp x_r, 10 b.lt top // Loop Finished

- Example

C Code:

04.4. The if construct

Formed by branching over the statement body if the condition is not true. Example:

if (a > b) { c = a+b; d = c+5; }Equivalent Assembly Code:

define(a_r, x19) define(b_r, x19) define(c_r, x19) define(d_r, x19) ... cmp a_r, b_r // test b.le next // Logical compliment add c_r, a_r, b_r add d_r, c_r, 5 next: // Statements after if conditionThe if-else construct is formed by brnaching to the else part if the condition is not true.

Example C Code:

if (a>b) { a = a+b; } else { a = a-b; }Equivalent Assembly Code:

define(a_r, x19) define(b_r, x20) cmp a_r, b_r b.le else add a_r, a_r, b_r b next else: sub a_r, a_r, b_r next: // Statements after the if-else construct

Session 05: Revise & Practice

Session 06: Bitwise and Shift Instructions

06.1. Bitwise Instructions

In computer programming, a bitwise operation operates on a binary number at the level of its individual bits. (A bit-by-bit operation)

Binary OR, | shorthand

0101 (decimal 5) OR 0011 (decimal 3) = 0111 (decimal 7)Binary AND, & shorthand

0110 (decimal 6) AND 1011 (decimal 11) = 0010 (decimal 2)Binary NOT, ~ shorthand

NOT 0111 (decimal 7) = 1000 (decimal 8)Binary XOR, ^ shorthand

0101 (decimal 5) XOR 0011 (decimal 3) = 0110 (decimal 6)

ARMv8 bitwise commands

- Or: ORR

- And: AND

- Xor: EOR

- Not: MVN (move and not)

Example

// Load Registers

mov x19, 0b0101

mov x20, 0b0011

// Perform bitwise Operations

orr x0, x19, x20

and x0, x19, x20

eor x0, x19, x20

mvn x0, x19, x20

06.2. Shift Instructions

- Left Shift

0101 << 1 = 1010 - Right Shift]

0101 >> 1 = 0010

Arithmetic Shift Preserves the sign bit (Leftmost bit). i.e. it does not move the leftmost bit

ARMv8 Shift instruction

- Logical Shift Left: LSL

- Logical Shift Right: LSR

- Arithmetic Shift Right: ASR

Example

// Load Registers

mov x19, 0b0101

mov x20, 0b0011

// Perform bitwise Operations

lsl x0, x19, 1

lsr x0, x19, 1

asr x0, x19, 1

Session 07, 08: Revise & Practice

Session 09: Stack Memory

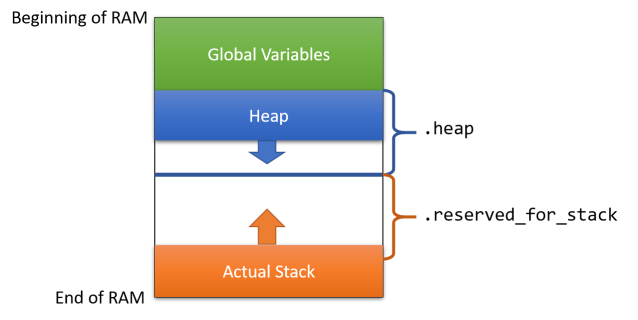

09.1. Memory Organisation

- Global Variables declared outside functions/methods are placed directly after each other starting at the beginning of RAM.

- Local (automatic) variables declared in functions and methods are stored in the stack.

- Variables allocated dynamically (vie the malloc() function or the new() operator) are stored in the heap.

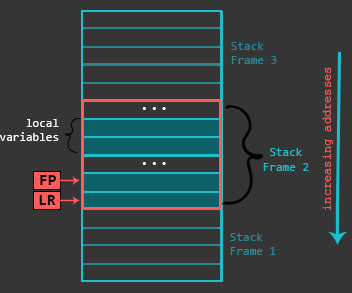

09.2. Stack Memory

- Frame Pointer (FP/x29) points to the starting address of the current stack frame. It is set once at the beginning of the function and does not change through the function.

- Link Register (LR/x30) points to the instruction from where a function was called. It is set when using the bl instruction. It is used to go back to the calling function after return.

- Stack Pointer (sp) points to the starting address of the stack which included temporary variables declared during the function. The sp register is decremented as variables are created and it is incremented as local variables go out of scope.

Making a function

- Move the stack pointer back to make room for local variables and calling function's FP & LR.

[sp, -16]! - Store Calling functions FP & LR at the starting of stack (SP).

stp x29, x30, [sp, -16]! - Store the new SP value to current FP.

mov x29, sp - Function body ....

- Load calling functions FP & LR from the starting of stack (SP) to x29, x30

ldp x29, x30, [sp] - Increment SP to the original position.

ldp x29, x30, [sp] - Return

09.3. Local Variables

Local variables are stored in the same manner as calling function's FP and LR are stored.

C Code:

int main() {

int a=10;

printf("Value of a = %d \n", a);

return 0;

}

Equivalent Assembly Code:

fmt:

.string "Value of a = %d \n"

a_s = 16 // Start of a

alloc = -(16+4) & -16 // Bytes to alloc (negative number will be added to decrement SP)

.global main

.balign 4

main:

stp x29, x30, [sp, alloc]! // Increment SP by -(16+4) & -16

mov x29, sp // Set current FP to new SP

// int a = 10;

mov w19, 10 // Store 10 temporarily in w19

str w19, [x29, a_s] // Load 10 at (sp + 16)

// printf("%d", a);

ldr x0, =fmt // First arg = address of format string

ldr w1, [x29, a_s] // Second arg = value stored at (sp + 16)

bl printf // Call printf

exit:

mov x0, 0 // Set return value 0

ldp x29, x30, [sp], -alloc // Restore Values from (sp) to x29 and (sp+8) to x30. Restore SP

ret

09.4. GDB Inspect Memory (x command)

The x command in GDB is used to view the content of RAM at a specific address. It has 3 modes.

x [Address]x/[Format] [Address]x/[Length][Format] [Address]

Example:

x/g $spView the 8 bytes of memory at address stored in stack pointer (Top of stack).- x/10g $sp View 8 bytes of memory 10 times starting from address stored in SP.

- x/dw $fp+16 View 4 bytes (w) of memory in decimal (d) at 16 bytes ahead of Frame Pointer ($fp+16)

Session 10: Revise & Practice

Session 11: Stack Memory - Arrays

11.1. Allocating arrays in the stack

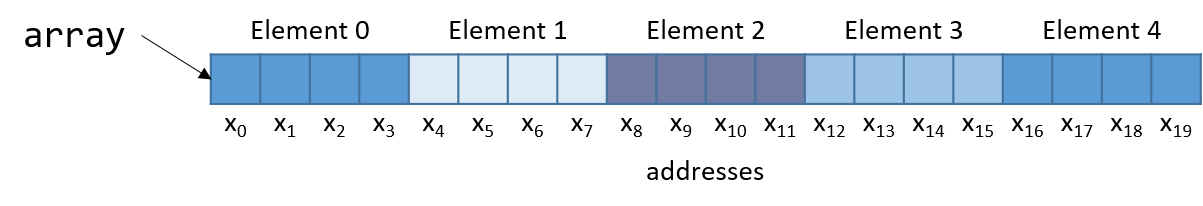

What are Arrays?

Arrays are ordered collections of data elements of the same type that are contiguously stored in memory.

Accessing Array Items

To get the address of item in an array from index i. Add the offset of the item to the base address.

Base Address : Address of the first byte of the array.

Offset: (index * item_size) The distance in bytes of the item from the base address.

*Address of arr[i] = Base + (i * item_size)*

Example:

- Address of Element 0 = Base + (0 * 4) = Base + 0

- Address of Element 1 = Base + (1 * 4) = Base + 4

- Address of Element 2 = Base + (2 * 4) = Base + 8

- Address of Element 3 = Base + (3 * 4) = Base + 12

- Address of Element 4 = Base + (4 * 4) = Base + 16

Storing Array in the stack

Arrays are stored like local variables on the stack with a large size.

*Size of the array = Number of items * item_size*

Example C:

#define ARR_ITEMS 10

int main() {

int var;

int arr[ARR_ITEMS];

var = 3456;

arr[0] = 1234;

}

Example Assembly:

arr_items = 10

var_size = 4

alloc = -(16 + var_size + arr_items*4) & -16

.global main

.balign 4

main: stp x29, x30, [sp, alloc]!

mov x29, sp

mov w19, 3456

str w19, [x29, 16]

mov w19, 1234

str w19, [x29, 20]

exit: mov x0, 0

ldp x29, x30, [sp], -alloc

ret

11.2. Loading & Storing Array Items

Array items can be loaded and stored in the RAM just like any other variable using the ldr and str instructions.

For getting the address of item we can use the offset = (index * item_size):

define(base_r, x19)

define(index_r, x20)

define(offset_r, x21)

# Calculate Base Address

add base_r, x29, arr_s

# Caclculate offset using mul

mul offset_r, index_r, 4

# Or Calculate offset using LSL (efficient)

lsl offset_r, index_r, 2

# Store w21 to arr[i]

str w21, [base_r, offset_r]

Note: Shift left by 2 is equivalent to multiplying by 4.

Offset can also be calculated using the "Register with scaled register offset" addressing mode

ldr val_r, [base_r, index_r, LSL 2] ; val_r = *(base_r + (index_r << 2))

For preserving sign in the index_r when shifting left, use the SXTW instead of LSL

ldr val_r, [base_r, index_r, SXTW 2] ; val_r = *(base_r + (index_r << 2))

Optimised Array Addressing:

define(base_r, x19)

define(index_r, x20)

# Calculate Base Address

add base_r, x29, arr_s

# Storing w21 -> arr[index]

str w21, [base_r, index_r, SXTW 2]

# Loading w21 <- arr[index]

ldr w21, [base_r, index_r, SXTW 2]

Exercise

Write a program in arm assembly to find the maximum item of an array. The array is initialised using the rand function.

C Code:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#define ARR_ITEMS 10

int main() {

int arr[ARR_ITEMS];

int i;

int max;

for (i=0; i<ARR_ITEMS; i++) {

arr[i] = rand() & 0xFF;

}

max = arr[0];

for (i=0; i<ARR_ITEMS; i++) {

if (arr[i] > max) {

max = arr[i];

}

}

printf("Maximum item is %d\n", max);

return 0;

}

Session 12: Revise & Practice

Session 13: Structures and Subroutines

13.1. Multidimensional Arrays

Most languages use row major order when storing arrays in RAM.

Row Major Order: In row-major layout, the first row of the matrix is placed in contiguous memory, then the second, and so on:

Offset of (r,c) = (r * NCOLS + c) * ITEM_SIZE

Where NCOLS is the number of columns per row in the matrix. It's easy to see this equation fits the linear layout in the diagram shown above.

int arr[2][3] (Multidimensional array with 2 rows and 3 columns)

Example:

int main() {

int arr[2][3];

register int i,j;

...

arr[i][j] = 13;

...

}

Assembly:

define(arr_base_r, x19)

define(offset_r, w20)

define(i_r, w21)

define(j_r, w22)

...

rows = 2

cols = 3

arr_size = rows * cols * 4

alloc = -(16 + arr_size) & -16

arr_s = 16

main:

stp x29, x30, [sp, alloc]!

mov x29, sp

...

add arr_base_r, x29, arr_s // Caculate arr base address

mul offset_r, i_r, cols // offset = (i * NCOLS)

add offset_r, offset_r, j_r // offset = (i * NCOLS) + j

mov w24, 13

str w24, [arr_base_r, offset_r, SXTW 2]

13.2. Data Structures

Contains fields of different types. Each field is accessed using an offset from the base address of the struct.

Example:

struct rec {

int a;

char b;

short c;

}

Base of rec

|

V

---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---

| | | a | a | a | a | b | c | c | | |

---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---

^ ^ ^

| | |

Offsets: a:0 b:4 c:5

// Offsets

rec_a = 0

rec_b = 4

rec_c = 5

// Access fields of struct pointed by x19

ldr w20, [x19, rec_a]

ldsb w21, [x19, rec_b]

ldrsq w22, [x19, rec_c]

13.3. Subroutines

Subroutines allow us to repeat a set of instructions using different arguments

Open Subroutine : Code is inserted (duplicated) wherever the subroutine is invoked.

Closed Subroutines : Machine code is not copied, the cpu jumps to the single place where the code is in the RAM and returns back to the calling place once the subroutine is over.

4. Open Subroutines

Open subroutines are usually implemented using a macros (M4).

M4 macros are created using define and arguments are accessed within the macro using $1, $2 ...

Note: Use `' instead of '' or "" to create multiline macros

Example:

// Macro to increment a register by 1

define(increment, `

add $1, $1, 1

')

...

increment(x19) // Calling macro

// Expands to

add x19, x19, 1

...

Example:

// Macro to print array of integers

fmt_int32: .string "%d \n"

define(print_int32, `

ldr x0, =fmt_int32

mov w1, $1

bl printf

')

...

print_int32(w19)

// Expands to

ldr x0, =fmt_int32

mov w1, w19

bl printf

...

Session 14: Closed Subroutines

14.1. Closed Subroutines

Closed subroutines do not rely on macros. They are placed outside the main or any other subroutine.

Building a closed subroutine :

label: stp x29, x30, [sp, alloc]!

mov x29, sp

// Body of Subroutine

....

ldp x29, x30, [sp], -alloc

ret

- label: Name of the subroutine. Used with bl instruction

- alloc: Assembler equate denoting the size in bytes to allocate in the stack frame.

Invoking Closed Subroutine

Closed subrotuines are are invoked using the branch and linking bl instruction (Subroutine Linkage).

bl label

- The bl instruction stores the return address (PC+4) in link register (x30) and changes the sp to the label.

- The CPU then starts execution from the updated program counter (PC)

- The ret instruction loads address from LR (x30) back into PC.

Example:

void printHello() {

printf("Hello ");

}

void printWorld() {

printf("World \n");

}

void printMessage() {

printHello();

printWorld();

}

int main() {

printMessage();

return 0;

}

Equivalent Assembly Code

str_hello: .string "Hello "

str_world: .string "World \n"

.global main

.balign 4

printHello: stp x29, x30, [sp, -16]!

mov x29, sp

ldr x0, =str_hello

bl printf

ldp x29, x30, [sp], 16

ret

printWorld: stp x29, x30, [sp, -16]!

mov x29, sp

ldr x0, =str_world

bl printf

ldp x29, x30, [sp], 16

ret

// printMessage Function

printMessage: stp x29, x30, [sp, -16]!

mov x29, sp

bl printHello

bl printWorld

ldp x29, x30, [sp], 16

ret

// Main function

main: stp x29, x30, [sp, -16]!

mov x29, sp

bl printMessage

mov x0, 0

ldp x29, x30, [sp], 16

ret

When the first printf is invoked the stack would look like this:

| |

| |

x29 --------> |================|

+---| Prev FP | <---- printf

| | -------------- |

| | Prev LR |

| | -------------- |

| | local vars |

+-->|================|

+-----| Prev FP | <---- printHello

| | -------------- |

| | Prev LR |

+---->|================|

+---| Prev FP | <---- printMessage

| | -------------- |

| | Prev LR |

+-->|================|

+-----| Prev FP | <---- main

| | -------------- |

| | Prev LR |

| |================|

+---->| |

| . |

| . |

| . |

| |

Arguments and Return Values to closed subroutines

- Arguments are passed using x0-x7 registers

- Single Return value is stored in x0 register

To pass in parameters to a subroutine, we generally use w0-w7 or x0-x7. It is possible to return multiple values as well by storing the return values in w0-w7 or x0-x7. The reason is simple: there is only one set of registers, and they are considered global. If a subroutine stores values in w0-w7, they will still be available to the calling code once the subroutine returns. Note that this is not true for all registers, and that w0-w7 are specificly used for passing parameters to/from subroutines.

Example: Program to calculate integer exponent using a function

C Code:

#include <stdio.h>

int power(int base, int exp) {

register int result = 1;

while(exp > 0) {

result = result * base;

exp--;

}

return result;

}

int main() {

int r;

r = power(5, 3);

printf("Result : %d \n", r);

return 0;

}

Equivalent Assembly Code in ex2.asm

Pointer Arguments

As we know pointers are just memory address so they will be stored in 64 bit registers (x0-x7) instead of 32 bit registers.

It implies that the variable value is in ram at the address stored in the argument.

Example: Program to swap 2 numbers using pointers passed to functions

C Code:

void swap(int *x, int *y) {

register int temp;

temp = *x;

*x = *y;

*y = temp;

}

int main() {

int a = 5, b = 7;

printf("a = %d, b = %d", a, b);

swap(&a, &b);

printf("a = %d, b = %d", a, b);

return 0;

}

Equivalent Assembly Code in ex3.asm

14.2. Exercise

Change Example 2 to take base and exponent from the terminal, using the scanf function

#include <stdio.h>

int power(int base, int exp) {

register int result = 1;

while(exp > 0) {

result = result * base;

exp--;

}

return result;

}

int main() {

int b, e, r;

// Use scanf to get users input

scanf("%d", &b);

scanf("%d", &e);

r = power(b, e);

printf("Result : %d \n", r);

return 0;

}

Session 15: Subroutine arguments and returned values

15.1. Passing/Returning Struct Value

Structs are mostly bigger than 8 bytes. Hence, they cannot be passed/returned in registers (x0-x7).

Returning struct value

- The calling code allocates, the memory for the returned struct in it's stack and stores the address of the allocated struct in x8.

- The invoked function then modifies the struct at the memory pointed by x8.

Example: C Code

struct color {

int r;

int g;

int b;

}

struct color black() {

struct color newcol;

newcol.r = 0;

newcol.g = 0;

newcol.b = 0;

return newcol;

}

int main() {

struct color col;

col = black();

printf("Color( r=%d, g=%d, b=%d )\n", col.r, col.g, col.b)

return 0;

}

Equivalent Assembly Code:

str_fmt:.string "Color( r=%d, g=%d, b=%d )\n"

.global main

.balign 4

// Define constants for struct col

color_size = 12

color_r_s = 0

color_g_s = 4

color_b_s = 8

define(col_base_r, x21)

main_alloc = -(16 + color_size) & -16

col_s = 16

main: stp x29, x30, [sp, main_alloc]!

mov x29, sp

// Store address of col in x8

add x8, x29, col_s

bl black

add col_base_r, x29, col_s

ldr x0, =str_fmt

ldr w1, [col_base_r, color_r_s]

ldr w2, [col_base_r, color_g_s]

ldr w3, [col_base_r, color_b_s]

bl printf

mov x0, 0

ldp x29, x30, [sp], -main_alloc

ret

define(newcol_base_r, x21)

black_alloc = -(16 + color_size) & -16

newcol_s = 16

black: stp x29, x30, [sp, black_alloc]!

mov x29, sp

// Calculate local struct base

add newcol_base_r, x29, newcol_s

str wzr, [newcol_base_r, color_r_s]

str wzr, [newcol_base_r, color_g_s]

str wzr, [newcol_base_r, color_b_s]

// Copy local struct to struct at [x8]

ldr w19, [newcol_base_r, color_r_s]

str w19, [x8, color_r_s]

ldr w19, [newcol_base_r, color_g_s]

str w19, [x8, color_g_s]

ldr w19, [newcol_base_r, color_b_s]

str w19, [x8, color_b_s]

ldp x29, x30, [sp], -black_alloc

ret

Passing struct value

Passing struct by value is done using the same method as returning struct by value. The address of the local variable to pass is stored in x0-x7. The subroutine then copies the struct to its stack from x0-x7.

Example 2: ex2.c, ex2.asm - Program to lighten color passed as value and return new color

15.2. Passing/Returning Struct Pointer

Passing by value is not very efficient, since the whole struct is copied before passing or returning. But it also makes sure that the original struct is not modified.

But sometimes, we might need to modify the original struct passed to the subroutine or we might neeed to just read the struct. In such cases, we do not need to allocate the struct in the subroutine's stack frame. Instead, we can pass the base address of the struct (pointer) and directly modify the memory at the address passed.

Example 3: ex3.c, ex3.asm - Modify example 2 lighten function to modify the original color passed instead of creating a new color.

Session 16: Revise & Practice

Session 17: External Pointer Arrays

17.1. External Pointers

Pointers are variables which store the address of another variable in memory.

Example:

void increment(int *ptr) {

*ptr = *ptr + 1;

}

int main() {

int i = 5;

int *ptr_i = &i;

printf("i = %d\n", i);

increment(ptr_i);

printf("i = %d\n", i);

return 0;

}

External Pointers are pointers which point to a variable not in the stack memory.

Example: a string literal is defined outside the stack. We just pass the address of the string to printf.

Example:

int main() {

// String literals are not stored in the stack.

char *msg1 = "Hello ";

char *msg2 = "World!\n";

// First argument to printf is a pointer to a string (char *)

printf(msg1);

printf(msg2);

}

Example:

msg1: .string "Hello "

msg2: .string "World!\n"

.global main

.balign 4

ptr_size = 8

alloc = -(16 + ptr_size + ptr_size) & -16

msg1_s = 16

msg2_s = 24

main: stp x29, x30, [sp, -16]!

mov x29, sp

// char *msg1 = "Hello ";

ldr x21, =msg1

str x21, [x29, msg1_s]

// char *msg2 = "World!\n";

ldr x21, =msg2

str x21, [x29, msg2_s]

// printf(msg1);

ldr x0, [x29, msg1_s]

bl printf

// printf(msg2);

ldr x0, [x29, msg2_s]

bl printf

exit: mov x0, 0

ldp x29, x30, [sp], 16

ret

17.2. External Pointer Arrays

External Pointer arrays are several pointers (address to variables in external memory) stored sequentially.

Defining external pointer arrays

arr_label: .dword ptr1 ptr2 ptr3 ...

Example:

str_jan: .string "January"

str_feb: .string "February"

str_mar: .string "March"

str_apr: .string "April"

str_may: .string "May"

str_jun: .string "June"

str_jul: .string "July"

str_aug: .string "August"

str_sep: .string "September"

str_oct: .string "October"

str_nov: .string "November"

str_dec: .string "December"

...

months: .dword str_jan, str_feb, str_mar, str_apr, str_may, str_jun, str_jul, str_aug, str_sep, str_oct, str_nov, str_dec

...

Accessing value inside external pointer arrays

Values inside external arrays are accessed using the same method as any other array:

address of i-th item = BASE_ADDRESS + INDEX * SIZE

For accessing values inside external pointer arrays SIZE = 8 bytes

address of i-th item = BASE_ADDRESS + INDEX * 8

Example:

define(base_r, x20)

define(index_r, x21)

ldr base_r, =months

ldr x21, [base_r, index_r, SXTW 3]

Note: We are using SXTW 3 since size of items inside array is 8 (2^3)

Data sections

- .text section is read only pre-initialized memory. It stores read only strings and assembly code.

- .data section is read-write pre-initialized memory. It stores global variables. Data section should be doubleword aligned.

Example:

// Store string literals in .text

.text

str_fmt: .string "months[%d] = %s\n"

str_jan: .string "January"

str_feb: .string "February"

str_mar: .string "March"

str_apr: .string "April"

str_may: .string "May"

str_jun: .string "June"

str_jul: .string "July"

str_aug: .string "August"

str_sep: .string "September"

str_oct: .string "October"

str_nov: .string "November"

str_dec: .string "December"

// Store global variables (pointer array) in .data section.

.data

.balign 8

months: .dword str_jan, str_feb , str_mar, str_apr, str_may, str_jun, str_jul, str_aug, str_sep, str_oct, str_nov, str_dec

// Store Code in .text section

.text

.balign 4

.global main

main: stp x29, x30, [sp, -16]!

mov x29, sp

mov w19, 0

loop_top: cmp w19, 12

b.ge loop_end

// printf("months[%d] = %s\n", w19, months[w19])

ldr x0, =str_fmt

mov w1, w19

ldr x20, =months

ldr x2, [x20, w19, SXTW 3]

bl printf

add w19, w19, 1

b loop_top

loop_end:

exit: mov x0, 0

ldp x29, x30, [sp], 16

ret

Session 18: Global Variables and Linking

18.1. Using .data and .bss section to store global variables

Global Variables

Global variables are variables which

- have a fixed place in memory

- they exist throughout the lifetime of the process

- they can be accessed from any function (globally)

In C, any variable defined outside the functions is a global variable.

Example (c):

#include <stdio.h>

int num = 10;

void printNum1() {

printf("num1 = %d\n", num);

num++;

}

void printNum2() {

printf("num2 = %d\n", num);

num++;

}

int main() {

printNum1();

printNum2();

printNum1();

printNum2();

return 0;

}

/* Output:

num1 = 10

num2 = 11

num1 = 12

num2 = 13

*/

Static Variables

static variables

- like global variables, have a fixed (static) place in memory

- unlike global variables, they are defined and used inside a function only

- unlike local variables, the value of static variables persists accross multiple calls of the same function.

Example (c):

#include <stdio.h>

void printNum1() {

static int num = 10;

printf("num1 = %d\n", num);

num++;

}

void printNum2() {

static int num = 10;

printf("num2 = %d\n", num);

num++;

}

int main() {

printNum1();

printNum2();

printNum1();

printNum2();

return 0;

}

/* Output :

num1 = 10

num2 = 10

num1 = 11

num2 = 11

*/

.data and .bss sections

+---- +======================+

: | |

: | | Read-Only memory

: | .text | Stores Instructions

: | | Stores String Literals

: | |

: +----------------------+

: | |

: | | Read-Write memory

Global Memory---+ | .data | Stores pre-initialized global variables

: | |

: | |

: +----------------------+

: | |

: | | Read-Write memory

: | .bss | Stores zero-initialized global variables

: | |

: | |

+--- +======================+

| |

| |

| HEAP |

| |

| |

+======================+

| |

| |

| STACK |

| |

| |

+======================+

- .text section are meant to store (constant) string literals and instructions

- .data and .bss sections are meant to store global variables

- Pre-Initialized Data can be stores in these sections using these pseudo-ops:

.dword: Double Word (8 bytes).word: Word (4 bytes).hword: Half Word (2 bytes).byte: byte (1 byte)

- Uninitialized space can be allocated using

.skippseudo-op followed by the number of bytes. Use this inside .bss section.

Example:

// Pre-Initialized Single Value

var1: .word 1234

// Pre-Initialized Multiple Values (Array)

arr1: .word 1, 2, 3, 4

// Uninitialized Space (E.g. for an int - 4 bytes)

var2: .skip 4

// Uninitialized Space (E.g. for an int array - 4 * 10 bytes)

arr2: .skip 4 * 10

Example 1 (C):

#include <stdio.h>

int a = 5;

int b;

void printResult() {

printf("Sum = %d\n", a + b);

}

int main() {

printResult();

b = 10;

printResult();

return 0;

}

/* Output:

Sum = 5

Sum = 15

*/

Example 1 (Assembly) :

.text

str_fmt: .string "Sum = %d\n"

.data

a_m: .word 5

.bss

b_m: .skip 4

.text

.balign 4

define(addr_r, x19)

alloc_printResult = -(16 + 8*3) & -16

printResult: stp x29, x30, [sp, alloc_printResult]!

mov x29, sp

// Preserve addr_r, x21, x22

str addr_r, [x29, 16 + 8*0]

str x21, [x29, 16 + 8]

str x22, [x29, 16 + 8*2]

// Load a

ldr addr_r, =a_m

ldr w21, [addr_r]

// Load b

ldr addr_r, =b_m

ldr w22, [addr_r]

// Print a+b

ldr x0, =str_fmt

add w1, w21, w22

bl printf

// Restore addr_r, x21, x22

ldr addr_r, [x29, 16 + 8*0]

ldr x21, [x29, 16 + 8]

ldr x22, [x29, 16 + 8*2]

mov x0, 0

ldp x29, x30, [sp], -alloc_printResult

ret

.global main

main: stp x29, x30, [sp, -16]!

mov x29, sp

bl printResult

mov w21, 10

ldr addr_r, =b_m

str w21, [addr_r]

bl printResult

mov x0, 0

ldp x29, x30, [sp], 16

ret

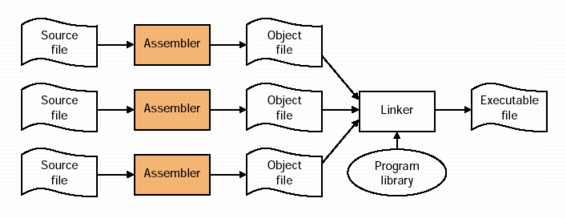

18.2. Separate Compilation

Till now we have written all of our code in one file. We can instead split our code into multiple files.

This allows us to:

- Avoid large confusing code files

- Put commonly used code in a common code file

- Invoke C from assembly and vice-versa

**Build process : **

- Assembling

- Each code file is compiled into object files individually.

- For C files, use the command

gcc c_code.c -o c_code.o -c - For assembly files, use the command

gcc asm_code.s -o asm_code.o -c

- Linking

- All the assembled object files are compiled into a single executable while also linking the required library code.

- Use the command

gcc c_code.o asm_code.o -o execfor linkingc_code.oandasm_code.o

Calling assembly code from c

Example 2

asm_code.asm:

.balign 4

.global sum // Make the function visible outside for linking

sum: add w0, w0, w1

ret

c_code.c:

#include<stdio.h>

// Declare the external function without body

extern int sum(int a, int b);

int main() {

register int a = 10;

register int b = 50;

printf("%d + %d = %d\n", a, b, sum(a, b));

return 0;

}

Terminal

# asm_code.asm -> asm_code.o

m4 asm_code.asm > asm_code.s

gcc -c asm_code.s -o asm_code.o

# c_code.c -> c_code.o

gcc -c c_code.c -o c_code.o

# c_code.o, asm_code.o -> build

gcc c_code.o asm_code.o -o build

# Run executable

./build

Calling C code from assembly

Example 3

c_code.c:

#include <stdio.h>

// These are defined in asm_code.asm

extern int a, b;

int swap(int *var1, int *var2) {

register int t = *var1;

*var1 = *var2;

*var2 = t;

}

void printAB() {

printf("a = %d, b = %d\n", a, b);

}

asm_code.asm:

.data

.global a

.global b

a: .word 23

b: .word 56

.text

.global main

.balign 4

main: stp x29, x30, [sp, -16]!

mov x29, sp

bl printAB

ldr x0, =a

ldr x1, =b

bl swap

bl printAB

exit: mov x0, 0

ldp x29, x30, [sp], 16

ret

Exercise

Create the above executable through separate compilation process

18.3. Using makefile for automating compilation

We can use makefile to automate the build process from inidividual source files to the final executable.

- Define the build process in a files named

Makefile - Use the

makecommand to run the build process fromMakefile

Example 3 : Simple Makefile

build:

# Create c_code.o

gcc -c c_code.c -o c_code.o

# Create asm_code.o

m4 asm_code.asm > asm_code.s

gcc -c asm_code.s -o asm_code.o

# c_code.o + asm_code.o --> build

gcc c_code.o asm_code.o -o build

Example 4 : Generic makefile

%.s: %.asm

m4 $< > $@

%.o: %.s

gcc -c $< -o $@

%.o: %.c

gcc -c $< -o $@

build: c_code.o asm_code.o

gcc $^ -o $@

18.4. Exercise

Crete a makefile to automate the above build process

Session 19: Command Line Arguments

19.1. Command Line Arguments

Command Line Arguments are arguments passed from the OS to a new process.

Passing Arguments through the linux shell

Syntax to pass arguments:

<PROGRAM_NAME> <ARG1> <ARG2> <ARG3> ...

- Any number of space separated arguments can be passed to the process.

- Each argument is of string (char *) type.

- The arguments are separated by a space or tab or any combination of both.

Example:

./a.out 1234 random_string 1234abc

Receiving arguments in a program

Arguments passed to the process are available in the form of arguments to the main function.

- The first argument (w0) is the number of arguments passed

- The second argument (x1) is a pointer to an array of arguments (strings)

- The first string in the list of arguments is the program name itself.

- Arguments start from the second item in the list of arguments.

Note: The array is an external pointer array. Each item of the array is a pointer to a string.

Example (c):

#include<stdio.h>

// argc (w0) : count of arguments

// argv (x1) : pointer to an array of pointers to arguments (strings)

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

register int i = 1;

while(i < argc) {

printf("argument %d = %s\n", i, argv[i]);

i++;

}

return 0;

}

/******************* Output should be similar to: ********

argument 1 = <arg1>

argument 2 = <arg2>

argument 3 = <arg3>

*/

19.2. ASCII to Integer (atoi) function

https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man3/atoi.3.html

The atoi function is used to convert a string (in ASCII code) to the integer it represents. e.g.: "1234" -> 1234

Example (c) :

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void)

{

register int i = atoi(" -9885"); /* i = -9885 */

printf("i = %d\n",i);

return 0;

}

/******************* Output should be similar to: ********

i = -9885

*/

Example (Assembly) :

str_num: .string " -9885"

str_fmt: .string "i = %d\n"

.global main

.balign 4

main: stp x29, x30, [sp, -16]!

mov x29, sp

// register int i = atoi(" -9885");

ldr x0, =str_num

bl atoi

mov w21, w0

// printf("i = %d\n",i);

mov x0, =str_fmt

mov w1, w21

bl printf

exit: mov x0, 0

ldp x29, x30, [sp], 16

ret

19.3. Using atoi() with command line arguments

All command line arguments are strings (Even if the user enters a number).

Use the atoi function to convert numeric strings to integers.

Example (c): Program to add two numbers passed as command line arguments.

#include <stdio.h>

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

register int num1 = atoi(argv[1]);

register int num2 = atoi(argv[2]);

printf("Sum = %d\n", num1 + num2);

}

str_fmt: .string "Sum = %d\n"

define(num1_r, w22)

define(num2_r, w23)

define(base_r, x20)

define(index_r, w21)

.global main

.balign 4

main: stp x29, x30, [sp, -16]!

mov x29, sp

mov base_r, x1

mov index_r, 1

ldr x0, [base_r, index_r, SXTW 3]

bl atoi

mov num1_r, w0

mov index_r, 2

ldr x0, [base_r, index_r, SXTW 3]

bl atoi

mov num2_r, w0

ldr x0, =str_fmt

add w1, num1_r, num2_r

bl printf

exit: mov x0, 0

ldp x29, x30, [sp], 16

ret

19.4. Exercise

Write a calculator program in assembly that can either add or subtract two numbers. The input is given through the command line arguments. as follows:

- argument 1 : First number

- argument 2 : "+" or "-"

- argument 3 : Second number

$ ./my_calculator 14 + 25

Result = 39

$ ./my_calculator 14 - 25

Result = -11

Hint: For comparing a register to the ascii value of a character use : cmp $w23, '-'

int main (int argc, char *argv[]) {

register int num1 = atoi(argv[1]);

register int num2 = atoi(argv[3]);

register char operation = argv[2][0];

if (operation == '+') {

printf("Result = %d\n", num1 + num2);

} else if (operation == '-') {

printf("Result = %d\n", num1 - num2);

}

return 0;

}

Session 20: Revise & Practice

Session 21: I/O

21.1. System I/O

In linux all I/O devices such as networks, disks, mouse, keyboard are modeled as files, and all input and output is performed by reading and writing the appropriate files. Files can be opened in linux using system calls (Kernal functions). The kernal ensures safe and secure access to the requested file.

System Call

System call is like a subroutine call to execute privileged functions (such as opening a file). This is done by the svc instruction.

| x8 | Service Request | Documentation |

|---|---|---|

| 56 | openat | https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man2/open.2.html |

| 57 | close | https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man2/close.2.html |

| 63 | read | https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man2/read.2.html |

| 64 | write | https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man2/write.2.html |

Steps to perform System I/O:

- Open file - Open the file for the system I/O that you wish to perform using the

openatsystem call. - Read/Write file - Read/Write bytes from the file using the

readorwritesystem call. - Close File - Disconnects device (If needed) or any other cleanup if needed using the

closesystem call.

File descriptor is a handle to an opened file for a process.

21.2. Reading/Writing a file

Step 1. Open the file

int fd = openat(int dirfd, const char *pathname, int flags, mode_t mode);

- dirfd - Directory file description relative from where the file needs to be opened. Set this to AT_FDCWD (the value -100) if the path is relative to the current working directory.

- pathname - Path of the file to be opened.

- flags - Settings with which to open the file. Multiple setings are combined using the or ( | ) operator. Each setting is specified using a constant value.

- File operations needed. Choose exactly one of these.

Constant Value Description O_RDONLY 00 Read-Only Access O_WRONLY 01 Write-Only Access O_RDWR 02 Read/Write Access - Optional Flags. Can select multiple.

Constant Value Description O_CREAT 00100 Create file if it doesn't exist O_EXCL 00200 Fail if file exists O_TRUNC 01000 Truncate an existing O_APPEND 02000 Append to the file

- File operations needed. Choose exactly one of these.

- mode - Unix permission mode for the newly created file (If created). Use

0666in octal for read/write permission only to the owner (The user creating the file). https://chmodcommand.com/

Step 2. Read/Write File

// Rading

int bytes_read = read(int fd, void *buf, size_t count);

// Writing

int bytes_write = write(int fd, const void *buf, size_t count);

- fd - Opened file's file descriptor

- buf - Address of where to read/write data inside the process' memory.

- count - Number of bytes to read/write

- Return Val - Actual number of bytes read/wrote.

Step 3. Close File

int success = close(int fd);

- fd - Opened file's file descriptor to close.

Example 1 (c) - Writing an int to a binary file

#include <stdio.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main() {

// Step 1. Open file

register int fd = openat(AT_FDCWD, "input.bin", O_RDWR | O_CREAT, 0666);

int value;

register int bytes_write;

if (fd == -1) {

printf("Cannot open input.bin file for writing!\n");

return -1;

}

// Step 2. Write 4 bytes to file

value = 1234;

bytes_write = write(fd, &value, 4); // sizeof(value) -> 4

printf("Written %d bytes to file\n", bytes_write);

// Step 3. Close file

close(fd);

return 0;

}

Example 1 (asm) - Writing an int to a binary file

str_filename: .string "input.bin"

str_openfail: .string "Cannot open input.bin file for writing!\n"

str_written: .string "Written %d bytes to file\n"

// Syscall codes

define(syscall_openat, 56)

define(syscall_close, 57)

define(syscall_read, 63)

define(syscall_write, 64)

// File Open Constants

define(AT_FDCWD, -100)

define(O_RDWR, 02)

define(O_CREAT, 00100)

// Function macros

define(fd_r, w25)

define(bytes_write_r, w26)

alloc = -(16 + 4) & -16

value_s = 16

.balign 4

.global main

main: stp x29, x30, [sp, main_alloc]!

mov x29, sp

// Step 1. Open file

mov w0, AT_FDCWD

ldr x1, =str_filename

mov w2, (O_RDWR | O_CREAT)

mov w3, 0666

mov x8, syscall_openat

svc 0

mov fd_r, w0

// Check if there was error

cmp fd_r, 0

b.ge open_ok

ldr x0, =str_openfail

bl printf

mov w0, -1

b main_return

open_ok:

// value = 1234;

mov w19, 1234

str w19, [x29, value_s]

// Step 2. Write value to file

mov w0, fd_r

add x1, x29, value_s

mov w2, 4

mov x8, syscall_write

svc 0

mov bytes_write_r, w0

// Print bytes written

ldr x0, =str_written

mov w1, bytes_write_r

bl printf

// Step 3. Close File

mov w0, fd_r

mov x8, syscall_close

svc 0

main_return: ldp x29, x30, [sp], -main_alloc

ret

21.3. Exercise

Write a program to read an int (4 bytes) from a binary file - input.bin

Session 22: Floating Point Numbers

22.1. Floating Point Registers

- Floating point numbers are processed only using the floating point registers.

- d8-d15 are callee saved registers

- d0-d7 and d16-d31 may be overwritten by subroutines.

- d0-d7 are used to pass floating point arguments into a function

Table: Operand name for differently sized floats

| Precision | Size (bits) | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Half | 16 | Hn |

| Single | 32 | Sn |

| Double | 64 | Dn |

Figure: Arrangement of floating-point values

Use .single or .double pseudo-ops to allocate and initialize

.data

a_m: .single 0r5.0 // 4 bytes

b_m: .double 0r5.33e-18 // 8 bytes

array_m: .single 0r2.5, 0r3.5, 0r4.5 // 4*3 bytes

22.2. Floating Point Arithmetic

Loading and Storing FP registers

ldr s0, [base_r, offset_r] // Loads 4 bytes

str d1, [x29, 16] // Stores 8 bytes

Basic Floating Point Instructions

// Addition

fadd s1, s2, s3 // s1 = s2 + s3

// Subtraction

fsub s1, s2, s3 // s1 = s2 - s3

// Mutliplication

fmul s1, s2, s3 // s1 = s2 * s3

// Multiply negative

fnmul s1, s2, s3 // s1 = -(s2 * s3)

// Division

fdiv s1, s2, s3 // s1 = s2 / s3

// Multiply Add

fmadd s1, s2, s3, s4 // s1 = s4 + (s2 * s3)

// Multiply Subtract

fmsub s1, s2, s3, s4 // s1 = s4 - (s2 * s3)

// Absolute value

fabs s1, s2 // s1 = abs(s2)

// Negation

fneg s1, s2 // s1 = -s2

// Move register <- register

fmov s1, s2 // s1 = s2

// Move register <- immediate

fmov s1, 0.25 // s1 = 0.25

// Conversion

fcvt s1, d2 // s1 = d2

// Convert Float -> Integer

fcvtns w1, s2 // Convert to nearest signed integer

fcvtnu w1, s2 // Convert to nearest unsigned integer

// Convert Integer -> Float

scvtf s1, w2 // Convert signed integer to float

ucvtf s1, w2 // Convert unsigned integer to float

// Compare

fcmp s1, s2

fcmp s1, 0.0

Example (asm) : Divide 7.5 by 2.0

.data

x_m: .double 0r7.5

y_m: .double 0r2.0

res_m: .double 0r0.0

.text

...

// x = 7.5;

ldr x19, =x_m

ldr d0, [x19]

// y = 2.0;

ldr x19, =y_m

ldr d1, [x19]

// res = x/y;

fdiv d2, d0, d1

ldr x19, =res_m

str d2, [x19]

...

22.3. Exercise

Calulate the approximate value of PI $(\pi)$ using the formula. Print PI at each step upto 10 decimal places.

$\frac{\pi}{4} = \frac{1}{1} - \frac{1}{3} + \frac{1}{5} - \frac{1}{7} + \frac{1}{9} \dots$

Solution (c)

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

register double pi = 0;

register double den = 1;

while(1) {

pi += 1/den;

den += 2;

pi -= 1/den;

den += 2;

printf("PI = %.10f\n", 4*pi);

}

}

Solution (asm)

str_fmt: .string "PI = %.10f\n"

dzero: .double 0r0.0

.global main

.balign 4

define(pi_r, d10)

define(den_r, d11)

define(one_r, d12)

define(two_r, d13)

define(four_r, d14)

main: stp x29, x30, [sp, -16]!

mov x29, sp

// Utility constants

fmov one_r, 1.0

fmov two_r, 2.0

fmov four_r, 4.0

ldr x19, =dzero

ldr pi_r, [x19]

fmov den_r, 1.0

loop: // pi += 1/den; den += 2;

fdiv d21, one_r, den_r

fadd pi_r, pi_r, d21

fadd den_r, den_r, two_r

// pi -= 1/den; den += 2;

fdiv d21, one_r, den_r

fsub pi_r, pi_r, d21

fadd den_r, den_r, two_r

// printf("PI = %.10f\n", 4*pi);

ldr x0, =str_fmt

fmul d0, pi_r, four_r

bl printf

// Repeat forever

b loop

exit: mov x0, 0

ldp x29, x30, [sp], 16

ret